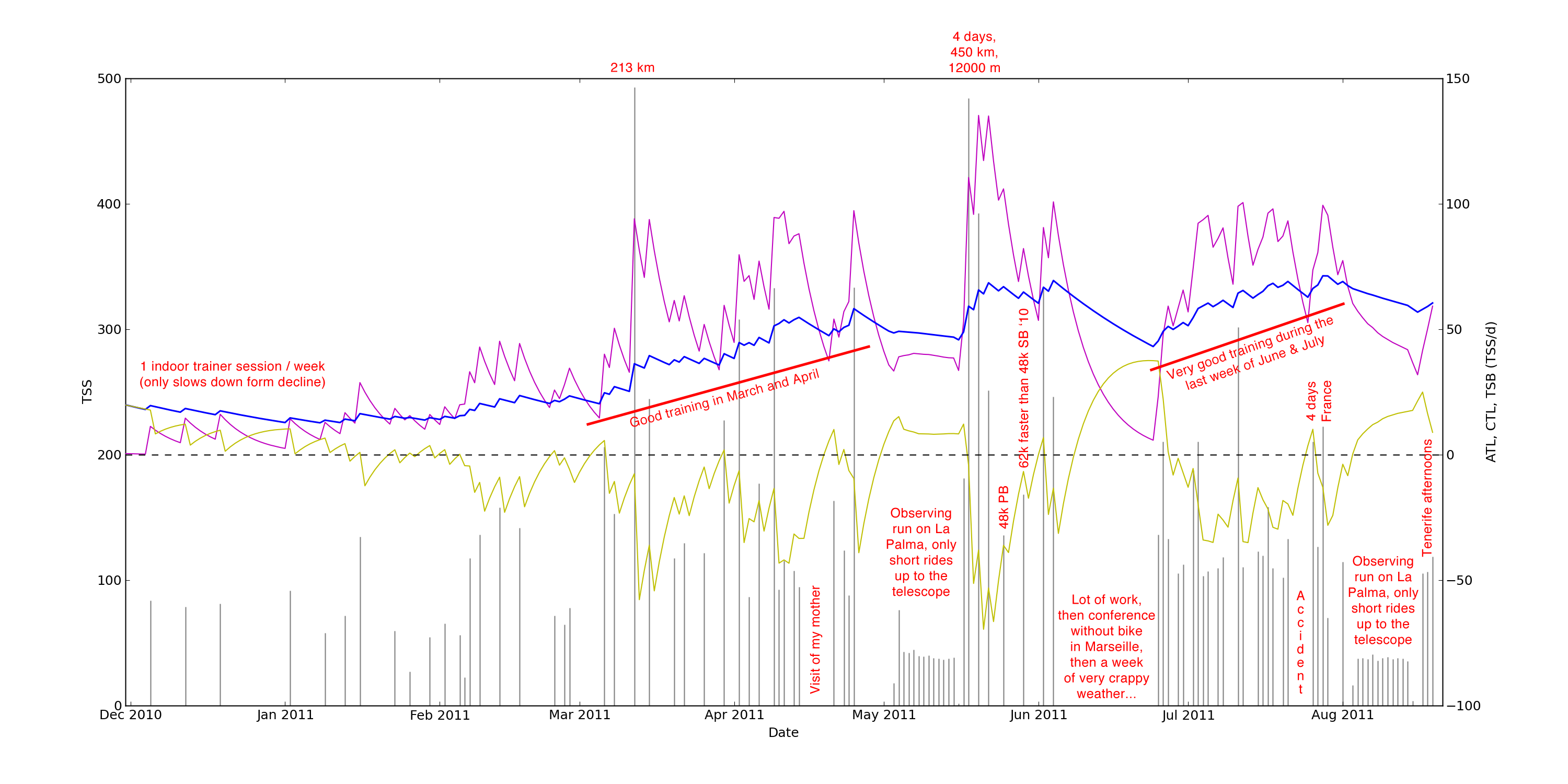

Updated 1: I modified the script slightly to perfectly match the estimation method of Joe Friel (see below), and as this had a small but clearly positive effect on the results, I have also updated the last plot and the paragraphs describing it at the end.

Updated 2: I have also tested the power estimate on very low intensity efforts with known average wattages (check out the bottom of the post).

You might remember that I have written a python script earlier this year, to analyze my cycling workouts and besides the calculation of detailed statistics, also create all kinds of fancy (multidimensional) plots. If you do not remember, or you would like to refresh your memories, please click here before reading this post further.

The most important thing missing from my script was the ability to directly compare different workouts. Of course you can tell that a 150 km ride with 5000 meters of elevation gain is more difficult than an easy 50 km Sunday afternoon ride, but how much more difficult? And what about an easy 75 kilometer training and a short but hard interval session? How do these compare? How tired am I going to feel myself after these? I really wanted to create or find a metric which tells me how much I did on a training. Of course this is only a problem when you don’t have a power meter installed on the bike, because that would directly tell you the amount of work in SI units for every workout. But power meters are expensive, and most importantly I don’t have one. This situation might change in the future, but till then let’s see what can we do.

I kinda forgot about the problem (and I did not even start dealing with it earlier, I just simply made a note on my To Do list), but some days ago Strava (a similar site to Garmin Connect, but with competitive – social media based – extras, unluckily with basically no users in Europe, so it is not an alternative for me) introduced a so called suffer score on their website, basically giving a rating to every ride based on its intensity (estimated from heart rate – HR – data) and duration. I knew that the algorithm behind this will be quickly decoded on one of the blogs I frequently read, and indeed it did happen very quickly, go and have a look there. First I wanted to implement this into my script, but then I got some extra motivation from the post and the comments there, so I looked a bit into the literature, and thus I got to know about the Training Stress Score, or simply TSS (among others, but this is the most important thing for us right now). To save some space here, check out the following three sites, so I can skip retyping things which are already on the Internet.

Estimating Training Stress Score (TSS), by Joe Friel

Normalized Power (NP), Intensity Factor (IF), and Training Stress Score (TSS), by Andrew R. Coggan, Ph.D.

What does 100 TSS mean, and the connection to Functional Threshold Power (FTP)

Though TSS and all these metrics are used in and based on power measurements, you can see that it is possible to give a good estimate (as good as estimating the realtive power on climbs from the slope gradient and VAM, which my script already did before) of it from time spent in HR zones using the scaling values from Joe Friel. We have seen that by definition a TSS of 100 equals to a one hour ride at FTP (so as hard as you can go for one hour). This means that rides shorter than one hour can have a TSS/hour higher than 100, but longer rides will have a lover value. So the TSS value tells you how big the training load of a given ride was (and it is related to the amount of post-ride fatigue), and the TSS/hour value gives you the intensity of your workout. The way it’s calcualted, TSS varies by the square of intensity. That means if you’re only going at 90% for an hour then you’re only accumulating 81 TSS per hour (90% = 0.9, which squared is 0.81, then you multiply by 100 to get TSS). So from the TSS/hour you can calculate an intensity factor, which gives you your average power output in units of your FTP power for the whole workout. Given that you know your FTP power, you can have a good estimate of the average power of any of your training rides! Now that is pretty cool. So that is what I have built into my script, this way now the TSS, TSS/h, average power and total work estimate values are also given in the summary file. And I also performed some test calculations and comparisons – because you should never forget, these are estimates! You need to know your FTP, and your HR at FTP, and then you might even get a reasonable value…

First of all, I wanted to see what is the intensity factor of my personal best ride to Mechelen and back. It was an approximately 1 hour 20 min all out effort, and the script gave an intensity factor of 1.00, meaning that I was riding on FTP. Though the ride was a bit longer than one hour (when it should not be possible to ride on FTP anymore), but I had a small 10 min break between the two legs in Mechelen, so it might still be a valid approximation, but for sure it should be extremely close to reality. Also, though it was a very tough ride, because it was short, the TSS value is ‘only’ 135.0, meaning that in 24 hours I might have probably almost fully recovered. In comparison, a normal ride (in my terms, so an average of 32 km/h instead of the record 35.7 km/h) on the same route gives a TSS around 110, while a recovery ride is probably below 100, and my epic ride (147 km and a bit more than 5000 meters of elevation gain) climbing twice up from sea level to the highest point of La Palma had a TSS of 483.7, which – as you have already guessed it probably – is in the epic category. Just as comparison, the last short (46 km and 400 meters of ascent) and recovery paced ride from France had a TSS of 69.5 (which is approximately half the TSS of my personal best ride which was done on an almost equally long, but completely flat route, so this really shows how easy this French ride was). So as I got an IF (intensity factor) of 1.00 on a ride which is very close to the definition of FTP I was already quite happy with the result. (If for such a ride you get something like 1.05 or even higher as IF, then that is a sign that your threshold heart rate is now higher, so you should change it accordingly in the parameter file.)

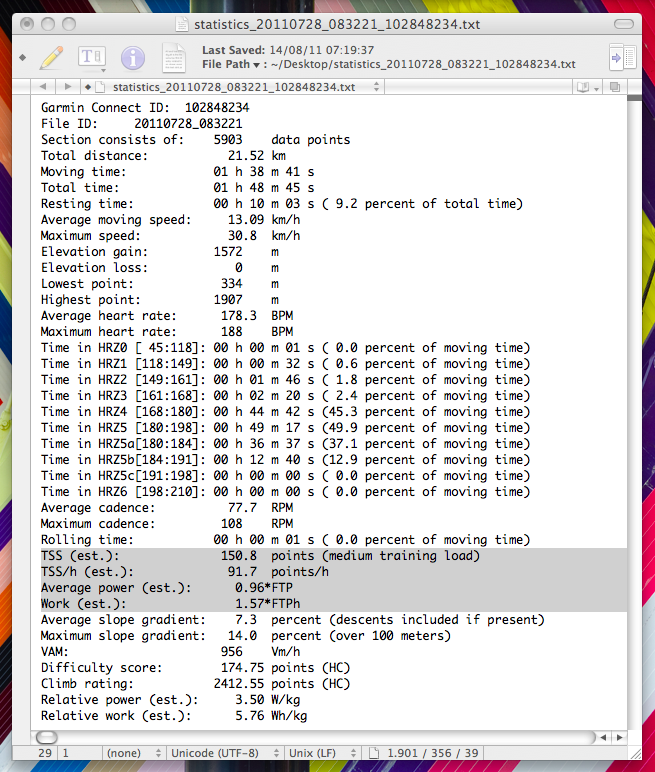

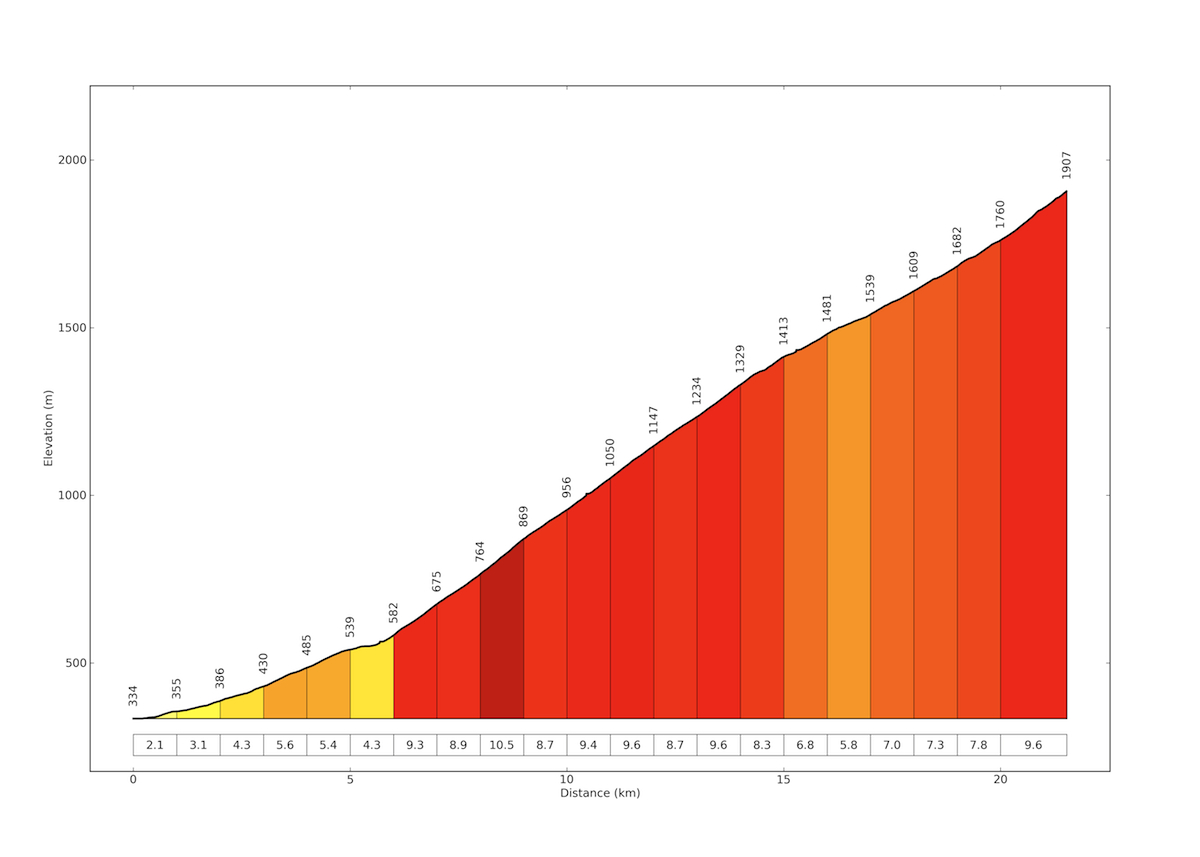

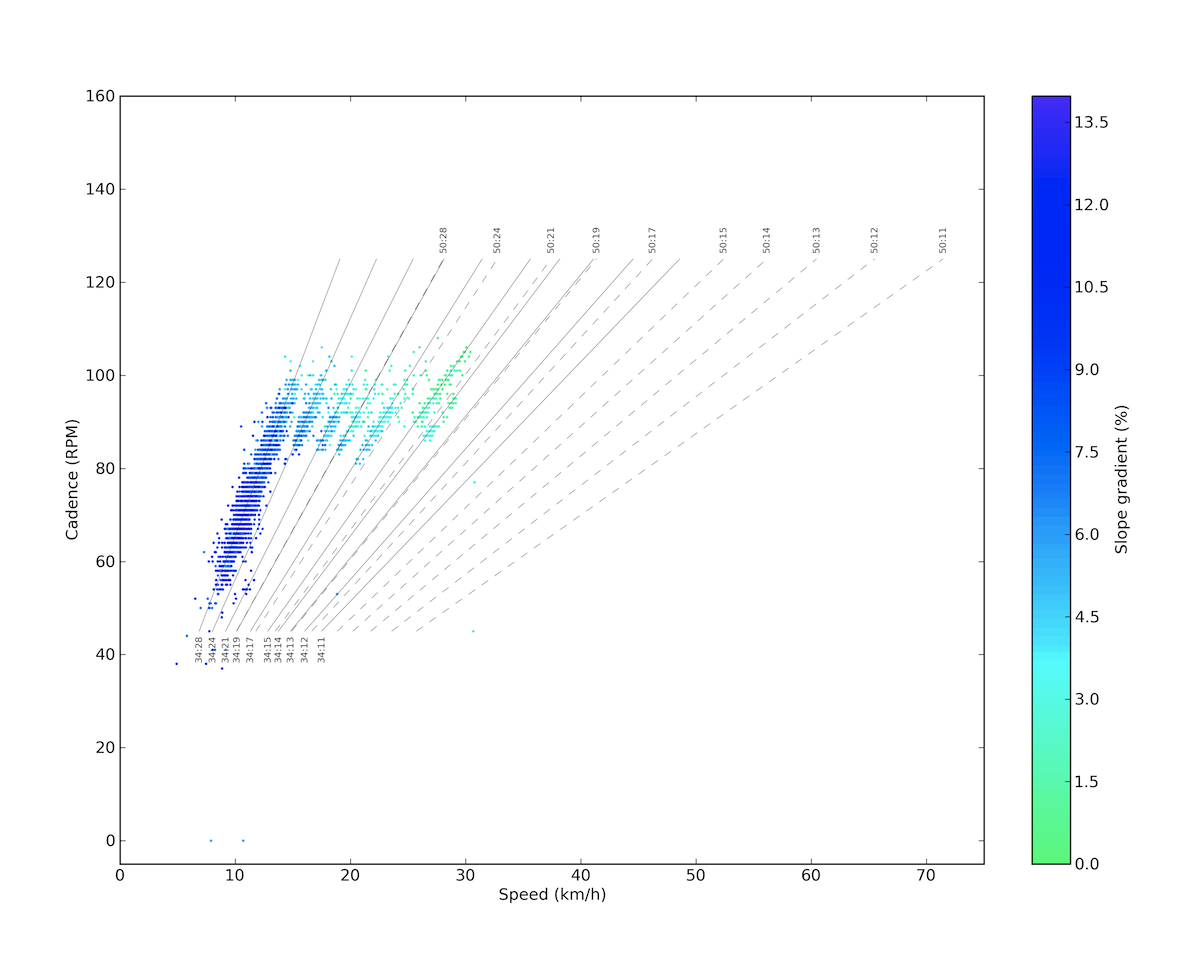

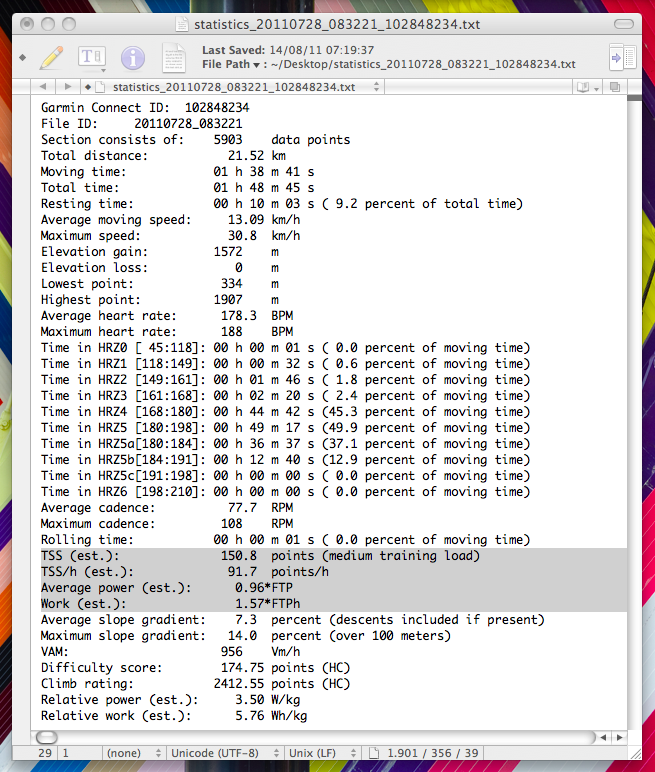

As a second test I wanted to see how does this power estimate compare to the power estimate from VAM and average gradient, which is a widely accepted and used relation for climbing sections. If the power values from the two methods match, then it is OK to use the power estimate from the hourly TSS value on rides even with no climbing at all. So first I took my recent ride up to the Mont Ventoux, where I did 1 hour and 40 minutes of all out riding, so I expect to get an IF around 0.95 and of course I am very interested to see how the two different power estimates will differ from each other (if they will differ at all). So here is the statistics file (recent additions marked with a grey background):

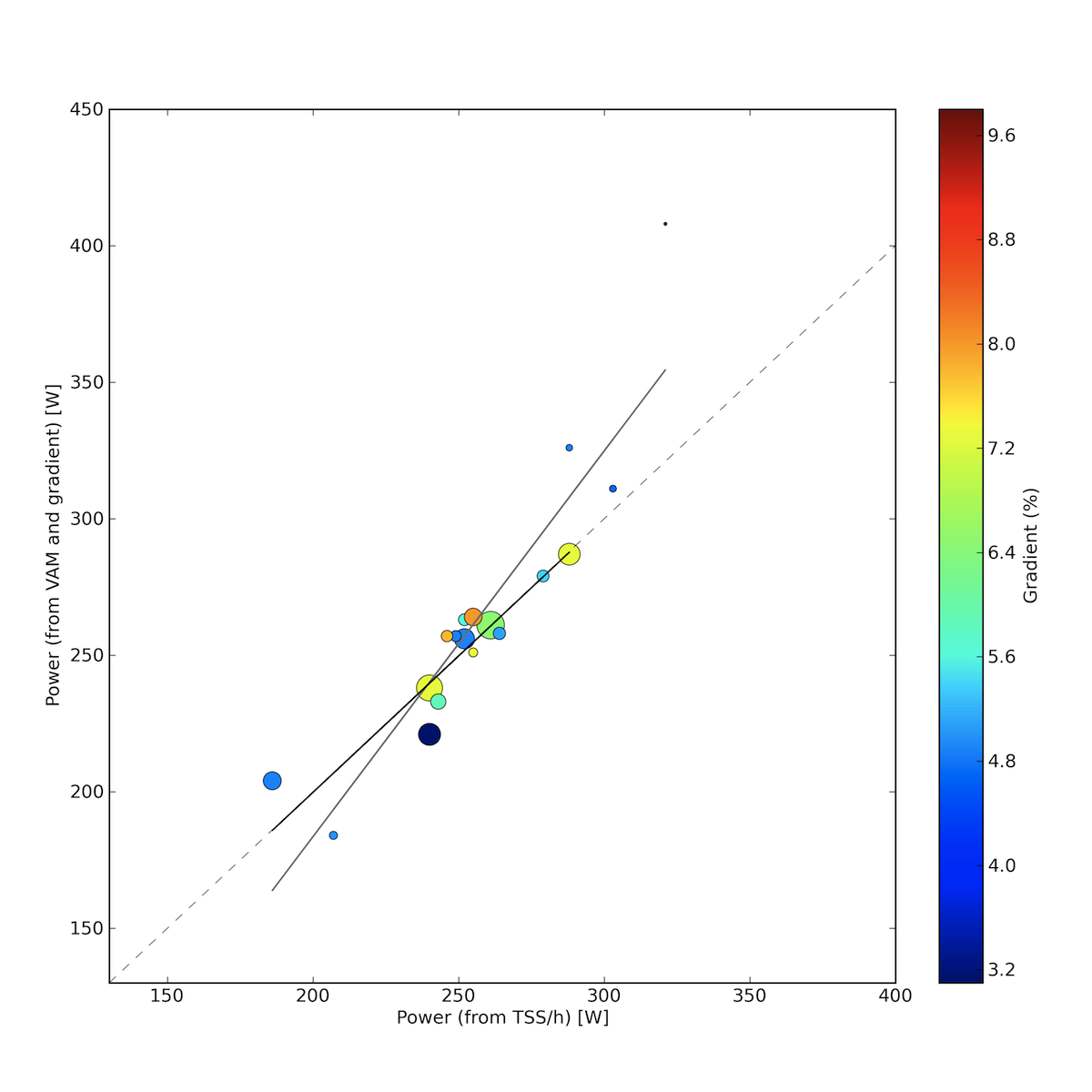

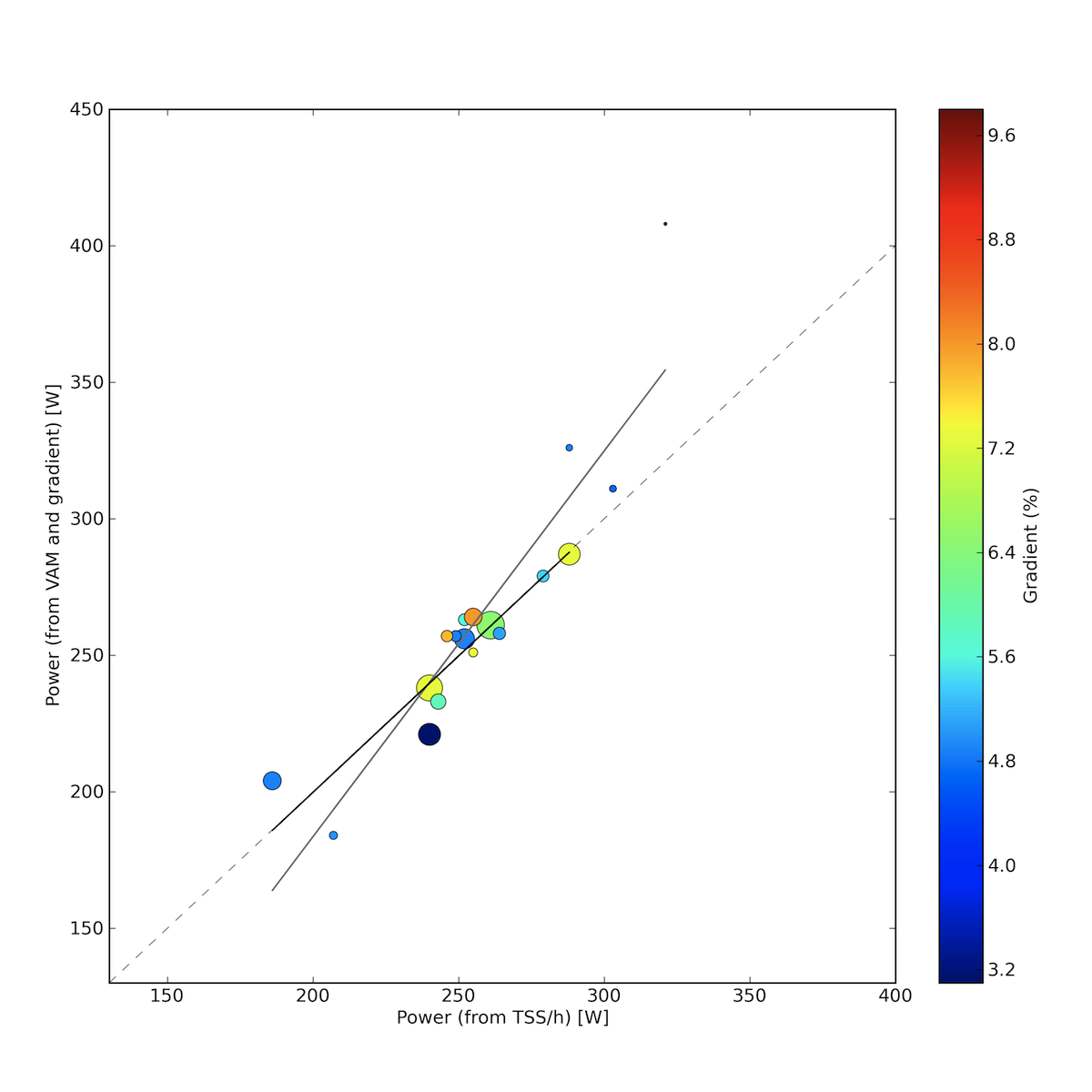

So from the IF of 0.96 you can see that indeed I did all I could in this time frame. Now we can estimate the average power from my FTP, which is somewhere around 300 W (or maybe a bit more, but I have to admit I don’t have a recent measurement, so I can only guess this from my workouts on the trainer back in the first months of the year). The result from this is 288 W. What about the value from the other method? I was ~70.5 kg and my bike + drink and food + clothes is an extra ~11.5 kg, then with a total weight of 82 kg and the relative power estimate from the VAM and gradient you get an average power of 287 W. These values are surprisingly almost perfectly identical! This means that I can most probably trust the TSS based method, and use it for complete rides, while the VAM and gradient based method only works on climb sections. This is quite nice! Of course one measurement is not a measurement, so I wanted to check this on other climbs as well. Unluckily I don’t have to many climbs (as Flanders is pretty flat), but I still managed to put together a sample of 18 climbs from this year, mostly from my rides on La Palma in may, and some others from later (so there is a chance that my FTP was not the same at the time of the different rides, but I still calculated with the same value, while for my total weight – with equipment included – I could make small changes based on me having a backpack with 2 extra liters of water or not). The sample has climbs from short explosive hills to the long ascents of La Palma, steep climbs and not so steep climbs, climbs where I was really fit and well recovered, and also climbs where I was tired, to see what is the effect of these on the relation. So all these climbs are displayed on the plot below (the size of the circles is related to the length of the climb, while the colour resembles the steepness).

With a perfect 1:1 relation between the two different power estimates we expect the climbs to fall on the x=y linear (which is the grey dashed line here). The correlation is well visible, with of corse some noise, but the trend seems to be pretty clear. The biggest outlier is the Smeysberg on the top right, which is a very short (430 meter) but very steep (an average of 9.8%) climb, and the reason why it is an outlier is that it was a sprint effort well above threshold, but starting with a very low heart rate, so it took some time till my HR got up into the regime which really corresponds to the level of my power output, and this time was in the order of the full length of the effort, so of course the TSS based metric is lower. For such sprint efforts the heart rate based estimated TSS will be always lower than the power based, because 1) the already mentioned lag of HR behind the sudden raise of power output, 2) that much above FTP the HR will not get higher, it does not matter if you maintain 400 W or 600 W for 30 seconds, your HR will be probably stuck at you maximum HR value. But these problems only arise when you do very short above threshold sprints. This is also why one of the small blue dots is also a clear outlier. Still, in the region where most of my training rides are (~220 W to 300 W) the match is almost perfect. Fitting a linear [y = f(x) = mx + b] to all the climbs (solid grey line) or only climbs which were longer than 3 km (a.k.a. efforts where there was a significant heart rate lag were dropped, thick black line) gives the following equations:

a) m = 1.41±0.16, b = -99±41, but we don’t really care about this

b) m = 1.00±0.12, b = 0±31, which is a perfect 1:1 match (with some noise of course)!

The other problem with HR based power estimates, that your heart rate at, e.g., 250 W will not be the same for two workouts which were ridden in different conditions, as for example dehydration and the level of residual fatigue strongly affects the heart rate. So again, these can significantly change the resulting estimated power. Like in case of the medium sized light blue circle slightly above the 1:1 line in the bottom left – this was a very slow paced ride (I was not alone), but I was extremely fit (after more than 1000 km ridden already in the same month, but basically no hard workouts in the previous one week), so probably my heart rate zones were a bit shifted. On the other hand, the two other climbs where the difference between the two values is larger than 5% (the small blue circle and the larger dark blue circle slightly below the 1:1 line towards the bottom left) were the last climbs of my two hardest days on La Palma, so at those ascents I was already very tired, which led to the shift of my HR zones – but now to the other direction. (At least this is my explanation.) Furthermore, small ascending sections can effect the estimate from overall VAM and slope gradient, and to convert relative power to power you need to know your total weight with bike, clothes, and everything included. Taking all these factors into account it is easy to understand why there is a scatter around the 1:1 relation.

To see what happens when you go to lower power – so the region of true recovery workouts – I have modified the script to be able to handle TCX files which do not contain GPS position information (so files which contain indoor trainer workouts). I have only three rides where I maintained a constant power instead of doing intervals (where the heart rate based method is clearly off, but we know that already), but in case of these, I can compare the ‘real’ average power (from the Tacx Flow) to the estimate. So for these three rides, the real average power values were 156 W, 140 W, and 200 W, while the estimates for the same rides are 133 W, 136W, and 220 W (assuming an FTP of 290 W as these were done very early in the season). The difference between the measurements and the estimates is in the order of ~10% (of the trainer values), which is OK for an estimate.

Conclusions: we can say that indeed the TSS based method can be used to estimate the average power (and workload) of workouts (even from HR data) if they do not consist of (only) short sprint efforts (so sections where there is a significant lag in the change of heart rate compared to the power output), as it scales well with another widely used power estimation method, and as it is consistent with wattage data from indoor trainer workouts (though the latter is only tested for low intensities). As a second conclusion: I really need a power meter (to test these estimates, and to have real power data, damn it)…

And oh, this was my 500th post!